Preserving and Teaching History through the Arts I

Several days ago our son John did an online performance of his popular “The Life of Laura Ingalls Wilder in Story and Song.” Though Ray and I rarely miss one of these, we weren’t available that day. When I asked John how the program went, he responded: “It was fun. I like to think I’m contributing something to help our society not become like that in The Giver.”

The Giver by Lois Lowry is a novel about a futuristic society which has created a government and social system with no freedoms, a society in which all possible situations have a government enforced solution. Among those solutions is euthanasia of children who don’t measure up to leaders’ expectations and of the elderly who have outlived their “usefulness.” No one even has the freedom to decide on a life work. Leaders assign each child a lifetime career when the child reaches age 12. One reason that leaders can exercise total control (which includes full-time surveillance of people, even in their own homes) is that all people are completely ignorant of history—all people, that is, except the book’s title character, the Giver.

Note: I think The Giver is an important book for parents to read aloud to teens because of the crucial issues it raises. Though many children read The Giver in the middle school grades, we don’t recommend it until high school. Notgrass History recommends it as a book for students studying our Exploring America for high school, but we have a parents’ guide which tells what portions of the book need parental oversight. Ray read it aloud to our family, and I believe that is the best way for students to learn the lessons in the book. Our hope is that the message of The Giver will help students when they become adults to recognize the dangers of losing any aspect of their freedom.

I appreciate John for sharing the history of Laura Ingalls Wilder with families through music. I am also thankful for George Catlin who shared the history of native nations with future generations through art. Music and art are two ways to capture children’s interest in history.

On Monday, while reading aloud about the land Meriwether Lewis, William Clark, and the Corps of Discovery passed through on their grand expedition of the Louisiana Purchase and about the native nations they encountered, I enjoyed seeing again the Catlin paintings that illustrate those lessons. Catlin said that he visited 48 different nations which included 400,000 people. In describing them, Catlin called them “400,000 souls.” He completed 310 oil portraits, along with a large collection of clothing and artifacts these nations created. William Clark aided George Catlin in his quest to complete those portraits. Sometime after the completion of Lewis and Clark’s Voyage of Discovery, the artist met William Clark in St. Louis. Clark took Catlin 400 miles up the Missouri River to Fort Crawford where members of several native nations were having a council. Catlin began painting portraits right away.

Today I want to share some of Catlin’s paintings with you. Each is courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum and were gifts of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr.

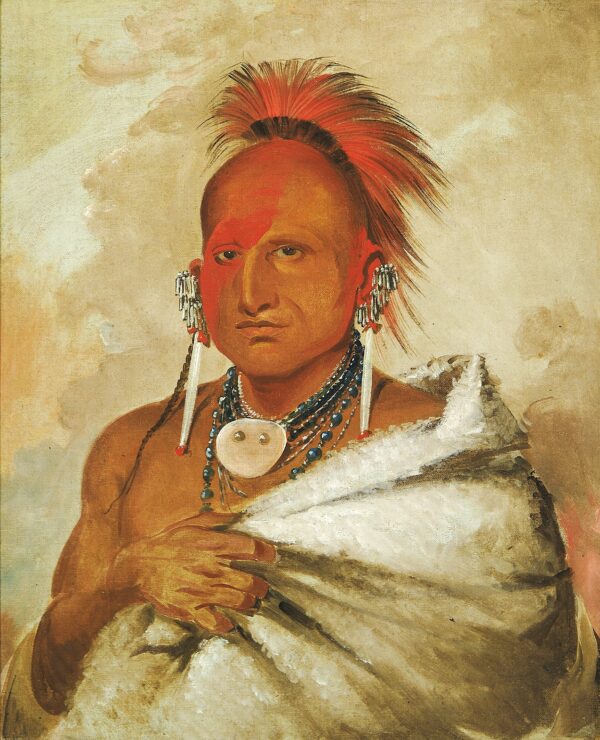

The Corps camped on the site of a Kansa village, but didn’t get to meet any members of the Kansa Nation at that time because they were away on a hunting trip. Catlin probably painted this image of the Kansa warrior O-rón-gás-see in 1832 at Fort Leavenworth, which is now in Kansas.

O-rón-gás-see, Bear-catcher, a Celebrated Warrior (Kansa) by George Catlin

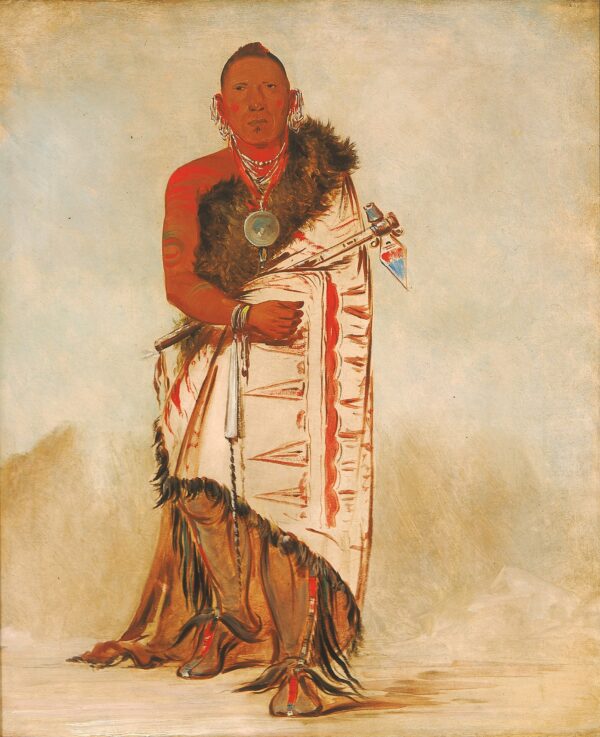

In August of 1804, the Corps passed an empty Omaha village. Its residents were away on a bison hunt. The only Omaha the Corps saw on their expedition were 48 Omaha prisoners the Teton Sioux had captured. Catlin probably painted this portrait of Omaha Ki-hó-go-waw-shú-shee at Fort Leavenworth in 1832 as well. Another American artist, Charles Bird King, also painted portraits of members of native nations. Between 1821 and 1842, King painted over 100 portraits of delegates of native nations who visited Washington, D.C. Around 1832, King painted a portrait of Ki-hó-go-waw-shú-shee.

Ki-hó-go-waw-shú-shee, Brave Chief (Omaha) by George Catlin

Of the native nations who lived in the Great Plains region, the Corps of Discovery spent more time with the Mandan than any other. Members of the Mandan Nation lived in two villages beside the Missouri River. A core belief of Mandan culture was that each village should work together for the benefit of the village and for each family and clan that lived there. At the center of the village was a central plaza. A cedar post that they believed to be sacred stood in the middle of the plaza. A medicine lodge stood at the northern end. Each village had 40 or 50 earth lodges. Each lodge housed about ten people.

In the fall, the Mandan hosted other Plains nations at a trade gathering. French and British traders came, too. Attendance was about 1,500 people. The Corps of Discovery arrived at the Mandan villages in November 1804, just after the fall trade gathering.

The Corps built their first winter camp nearby. They called it Fort Mandan and spent the winter of 1804-1805 there. The Mandan supplied food for the Corps in exchange for goods the Corps had brought on the expedition.

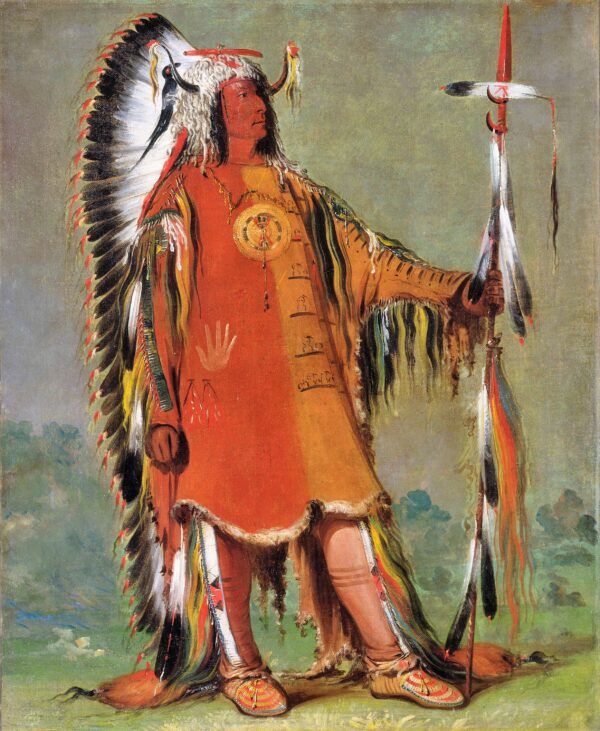

George Catlin visited a Mandan village in 1832. While there he asked Máh-to-tóh-pa to stand for a portrait. Máh-to-tóh-pa came to Catlin early the next morning. Many women and children escorted Máh-to-tóh-pa, who served as one of the village chiefs, to the door of Catlin’s dwelling in the village (Catlin mistakenly called the dwelling a wigwam). The artist described Máh-to-tóh-pa as a man who carried himself with grace and manly dignity, noting that he was handsome, brave, valiant, generous, elegant, and gentlemanly.

Máh-to-tóh-pa, Four Bears (Mandan) by George Catlin

I enjoyed reading Catlin’s description of Máh-to-tóh-pa. I like seeing how he portrayed this Mandan man’s dignity and other excellent traits in the portrait. The artist displayed many of his portraits in New York City in 1837. He called them his “collection of Nature’s dignitaries.”

The relationship between native nations and the American government would have been much improved if all Americans had seen native nations the way Catlin saw and portrayed them. I believe that when we see the dignity in each person we are actually seeing evidence that God created each of us in His image.

First of all, then, I urge that entreaties and prayers,

petitions and thanksgivings, be made on behalf of all men,

for kings and all who are in authority,

so that we may lead a tranquil and quiet life

in all godliness and dignity.

1 Timothy 2:1-2

I love The Giver series. I actually read The Giver with my son when the schools closed down in March 2020, when he was finishing up his 6th grade year. I never would have let him read it on his own at that age, but with my guidance it was a good learning experience, and seemed to fit right in with the dystopia we were living in at the time.