What is education anyway?

On Monday morning, our team member Titus and I continued to record lessons for our upcoming audio supplement for America the Beautiful. I love working with Titus, and it is really fun for me to get to read America the Beautiful aloud.

On Monday we were ready for Lessons 38 and 39, which teach about the Great Plains region that Lewis and Clark and the Corps of Discovery passed through on their expedition of the Louisiana Purchase, and about the native nations they encountered. I also read Lesson 40 about the life of Noah Webster. Noah Webster may seem like a strange topic to follow lessons about native nations and Lewis and Clark. However, Noah Webster published his first dictionary in 1806, which was the same year that Lewis, Clark, and the Corps of Discovery completed their journey to the Pacific Ocean and back.

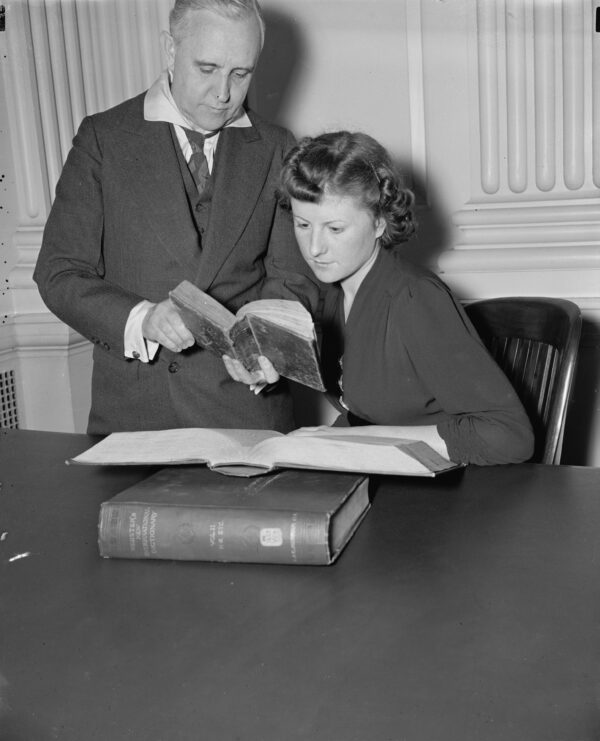

In the photo below, dated March 21, 1938, V. Valta Parma, who was then the curator of the Rare Book Division at the U.S. Congressional Library, shows Ethel Hearn a copy of the 1806 Webster dictionary.

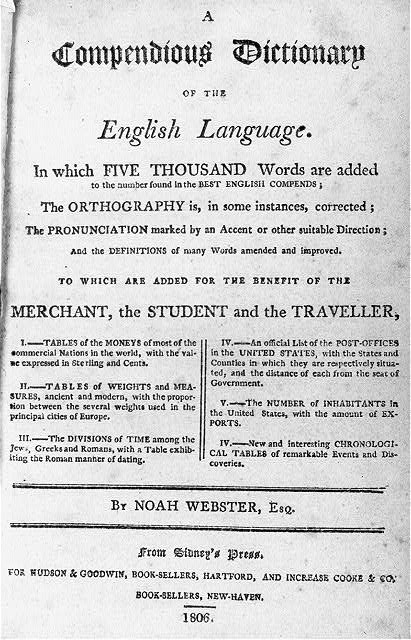

Title page: A Compendious Dictionary for the English Language, by Noah Webster, 1806

Both images are courtesy Library of Congress.

Wanting to confirm that the Library of Congress caption of the above photo was correct, I searched online for another photo of the 1806 edition and found one listed on ebay for $3,000 or best offer!

Webster graduated from Yale in 1778. He became an elementary schoolteacher and began to study law. He became convinced that Americans should have their own textbooks. He didn’t want students to be dependent on textbooks from England. This patriotic American thought American schoolbooks should contain American words, such as skunk, hickory, and chowder, and also American geography. Webster wanted to promote a truly American form of English.

Though Webster passed the bar and became a lawyer in 1781, he continued teaching and began to write a spelling book. He published it in 1783. People called it the Blue-Backed Speller. He published a grammar book in 1784 and a reader in 1785. Together the speller, grammar book, and reader were the three-volume Institute. The Institute showed the differences between American and British grammar, pronunciation, and spelling.

In 1785 and 1786, Webster traveled from one state to another to get people interested in his books. The Blue-Backed Speller sold all over America. It was the best-seller of his Institute series. Though the book was called a speller, parents and teachers also used it to teach children to read. Since children from many places grew up learning from the same book, children in different parts of America learned to pronounce and spell words the same way.

Webster wrote his first dictionary because he believed that America needed a dictionary with words Americans used every day, plus new scientific and technical words. Webster published A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language in 1806. This dictionary defined 37,000 words. About one-eighth of those words were new words American authors used. Americans were enthusiastic. They felt patriotic about Webster’s truly American dictionary.

Webster continued to publish new editions. He reviewed the Greek, Latin, and Hebrew he had learned in college. He did research in America, England, and France. He studied Anglo-Saxon, Danish, French, German, Old Irish, Persian, Welsh, and other languages to better understand the origins of English words. Webster wrote on paper with a quill pen. When he finished, he had defined 70,000 words. Webster published his final version of the American Dictionary of the English Language in two volumes in 1828, at age 70.

Noah Webster. Courtesy Library of Congress.

Webster helped many Americans gain knowledge. His influence on language and education has continued throughout America’s history. Webster’s 1828 dictionary has many quotations from the Bible. He often used a Bible quotation or a Biblical teaching to explain a word’s meaning.

Noah Webster died in 1843 at age 85. He and his wife are buried in West Hartford, Connecticut (in the same cemetery as Eli Whitney, inventor of the cotton gin). The following tribute is in the edition of Webster’s dictionary published ten years after his death:

But he will long be remembered by many . . . as the Christian moralist, “who taught millions to read, but not one to sin.”

As I read the lesson into the microphone on Monday, I was struck again by the brilliance of Webster’s definition of education. Though I shared this definition in Daily Encouragement in 2020, I’d like to share it again today.

EDUCA’TION, noun [Latin educatio.] The bringing up, as of a child, instruction; formation of manners. Education comprehends all that series of instruction and discipline which is intended to enlighten the understanding, correct the temper, and form the manners and habits of youth, and fit them for usefulness in their future stations. To give children a good education in manners, arts and science, is important; to give them a religious education is indispensable; and an immense responsibility rests on parents and guardians who neglect these duties.

What a great definition of a Christian homeschooling education.

Fathers, do not provoke your children to anger,

but bring them up in the discipline and instruction of the Lord.

Ephesians 6:4