Preserving and Teaching History Through the Arts III

Today I am sharing paintings that American artist George Catlin created of women, children, and homes of native nations. This is the last of my recent series on preserving and teaching history through the arts.

In the fall of 1804, Meriwether Lewis, William Clark, and the Corps of Discovery continued west on the Missouri River during their great Voyage of Discovery. On October 8, they came upon a three-mile-long island with three Arikara villages. About 2,000 Arikara lived there. The Corps stayed with them for five days.

The Arikara were excellent farmers. In years when their crops had low yields, they also hunted bison. In addition to beans, corn, and squash, they grew pumpkins, tobacco, and watermelons. Arikara women used tools made from bison or deer bones to take care of the crops.

The Corps had already met the Teton Sioux with whom the Arikara traded. The Arikara provided food and horses to the Teton Sioux. The Teton Sioux provided clothing and guns to the Arikara.

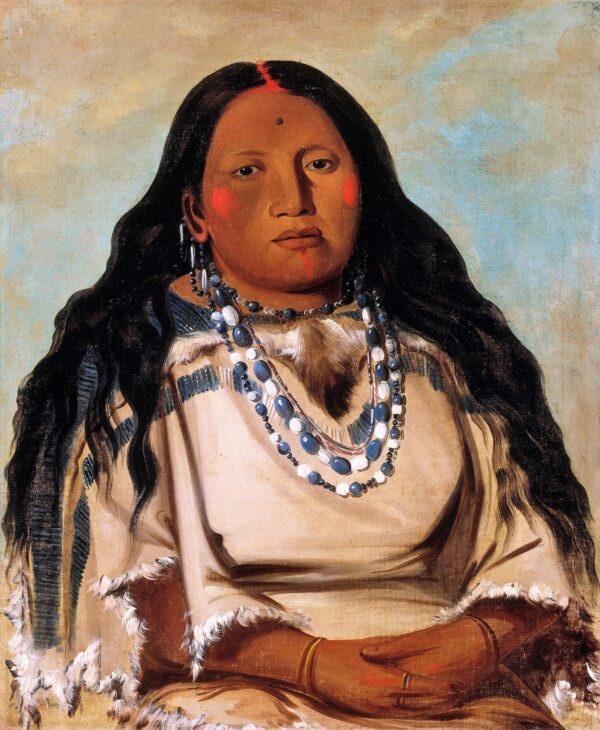

In 1832 Catlin visited a Mandan village. While he was there, he painted Kah-béck-a and her husband Bloody Hand, who was the Arikara chief. Catlin admired the dress that Kah-béck-a was wearing and purchased it for his collection of artifacts.

Kah-béck-a, The Twin, Wife of Bloody Hand (Arikara) by George Catlin

The Corps of Discovery did not meet members of the Kiowa nation, but they did mention that the Kiowa traded with the Arikara. George Catlin liked to portray the affection members of native nations had for the people in their families. He painted this Kiowa brother and sister at Fort Gibson in 1834. Fort Gibson was in what is now Oklahoma.

Túnk-aht-óh-ye, Thunderer, a Boy, and Wun-pán-to-mee, White Weasel, a Girl (Kiowa sister and brother) by George Catlin

The Corps of Discovery spent the winter of 1804-1805 in what is now North Dakota. They chose a location along the Missouri River nearby Mandan villages and built a fort there. Meriwether Lewis wrote, “This place we have named Fort Mandan in honour of our Neighbours.” While they were there, they met people from the nearby Hidatsa villages. They also met members of the Cheyenne, Assiniboine, and Plains Cree.

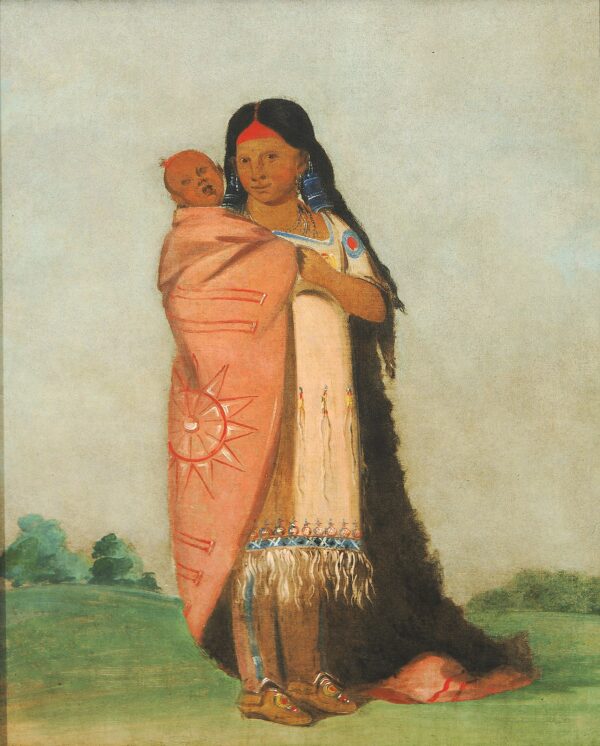

Catlin met members of the Plains Cree Nation while at Fort Union, where fur traders and native nations met to trade furs for the American Fur Company. The fort was near the confluence of the Yellowstone and Missouri Rivers. Catlin described the Cree as a very numerous people who traded at the fort. He called them “daring and most adventurous,” saying that they traveled vast distances over the prairies. Catlin painted this mother and baby while at Fort Union. He painted her in a full-length portrait in order to show how Plains Cree women cut and ornamented their dresses.

Tsee-moúnt, Great Wonder, Carrying Her Baby in Her Robe (Plains Cree) by George Catlin

The Corps also met members of the Assiniboine Nation during the winter of 1804-1805. Assiniboine is an Ojibwe word meaning “stone water people.” The Assiniboine used hot stones to boil water for cooking. These nomads were suspicious of Americans. Members of the Corps of Discovery were afraid of the Assiniboine. The Corps never encountered the Assiniboine in their own lands, though they saw evidence of where the nation had been .

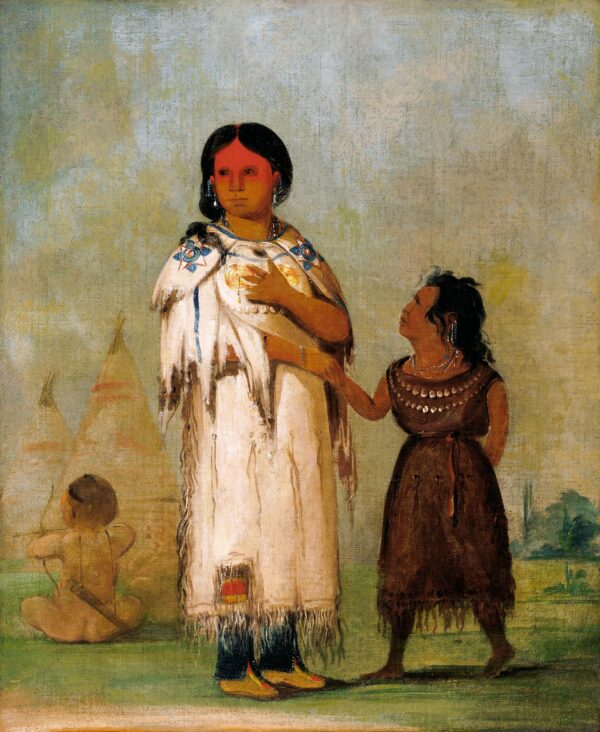

Catlin met members of the Assiniboine Nation at Fort Union. He wrote that their hair was very long, often reaching almost to the ground. However, he said that usually those with especially long hair had glued other hair onto their own hair and then covered the glued spots with red earth and glue. He later visited an Assiniboine village of tepees that was home to several thousand.

Catlin painted this Assiniboine woman while he was at Fort Union. He wrote: “The women of this tribe are often comely, and sometimes pretty.” He said that the clothing of Assiniboine women and children were usually made of the skins of the mountain goat and ornamented with porcupine’s quills and rows of elk’s teeth.

Assiniboine Woman and Child by George Catlin

Like many Plains nations, the Hidatsa lived in circular earth lodges. Many Plains nations lived in earth lodges for most of the year. As in other native nations, Hidatsa women were responsible for building their homes. Hidatsa women could complete a lodge in seven to ten days. One woman served as the construction supervisor. She laid out a circular floor plan and marked the place for each post. Women used stone tools to cut down cottonwood trees to use for posts and beams. Men helped the women put up the main posts and crossbeams. Can you imagine this next fact? After the men helped them put up the posts and beams, the women gave a feast to thank them for their help.

The women completed a frame for a circular wall and a roof. They covered the frame with split logs, willow branches, dry prairie grass, and sod. When a lodge was finished, the people celebrated another feast to thank all those who helped. The female supervisor received soft bison skin and other items as payment for her services.

In the Hidatsa Nation, each lodge was home to between 10 and 20 people. Usually sisters and their families lived together. Raised beds lined the outer wall. The beds had bison coverings and skin pillows, stuffed with grass or animal hair. Beds for adults had curtains made from old tepees. Marks of honor won by the husband decorated the curtains. The nation’s best horses shared the homes at night, staying in indoor corrals.

In the center of the home was the firepit. When rains or snows were heavy, the Hidatsa placed a bull boat over the roof hole and propped it up so the smoke could escape. Earth lodges lasted about ten years.

Catlin visited the Hidatsa and painted the following scene of one of their villages. He mentioned their many cornfields. He spoke of their paddling in the river in tub-like canoes that were made of bison skin and of both men and women being “passionately fond” of swimming. He told of their spending time in sweat houses and then leaping into the river.

In 1832 he painted this scene of Hidatsa swimming and paddling in the river below their earth lodges.

Hidatsa Village, Earth-covered Lodges on the Knife River by George Catlin

George Catlin worked to record the people of native nations and their lifestyles. So that others could see what he saw, he took those painted records back to the East and also to Europe. If Catlin could travel through time to the 21st century, I wonder how he would portray homeschooling mamas and daddies, brothers and sisters, and our homes. Native people often put on their best clothes to stand for their portraits. What clothing would we wear? What would he find to be unique in our homes? What objects would he include to define our lives? How would he portray what is most valuable to us?

As we think about these questions, let’s remember what Paul told the church in Ephesus:

Therefore I, the prisoner of the Lord, implore you to walk

in a manner worthy of the calling

with which you have been called,

with all humility and gentleness, with patience,

showing tolerance for one another in love,

being diligent to preserve the unity of the Spirit

in the bond of peace.

Ephesians 4:1-3

All paintings are courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum and were gifts of Mrs. Joseph Harrison Jr.